Modern Physics: Alex Monteith, Bas Jan Ader, Eddie Clemens, Hanna Schwarz, John Ward Knox, Philip Dadson, Shaun Gladwell. Curated by Stephen Cleland

Te Tuhi

10 October – 29 November 2009

The moving mass of a muscular human body is the theme of this mainly video international exhibition: firstly in how it senses its external relationship to its immediate spatial environment; secondly how it is internally aware of its own various extended components.

Such phenomenological themes might sound a bit dry, but in this show they are not at all. It is an inspired piece of curating by Stephen Cleland where the assembled artworks are deftly positioned in a convincingly cohesive sequence, and where there is an abundance of humour and aural and visual delight. This exhibition is so intriguing and so full of pleasant surprises you won’t want to leave.

In a newly furbished space opposite the Te Tuhi entrance Shaun Gladwell’s stunning video installation presents an inverted film of Og de Souza, a Brazilian skateboarder with stunted legs, sitting cross-legged on his board as he races through a carpark upside down - propelled only by his exceptionally strong arms. This imagery (with audio) is a foil to another (silent) film screened simultaneously at rightangles on another wall. In a nightclub in front of a bar, the glamorous leggy transvestite Grace O’Hara, an erotic pole dancer, gyrates alone in a tasselled bikini and high heels.

The contrasts between these two films (both with dominant horizon lines) are utterly absorbing: one with pulsing strobe-lights, other lit soft and even; the strip club with reflective steel, the carpark with matt concrete; the dancer leggy, the skateboarder legless; a ‘naked’ black ‘female’, a clothed white male; 'she' is upright, he inverted; one comparatively stationary, the other ‘pursuing’ at speed; the club referencing Francis Bacon’s theatrical cages, the boardrider alluding to Velasquez’s court dwarves.

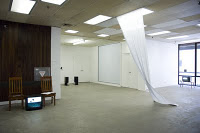

In the rest of Te Tuhi, in the main viewing area that you access between the bookshop and the library, are works by the six other artists. Just inside the double-glass doors are three b/w seventies videos by the legendary Dutch conceptual artist Bas Jan Ader (1942 -1975), exploring the body’s limitations with gravity. They try to hilariously construct T-shapes by attempting equilibrium.

In one film he tries to balance a large slab of concrete high up in the air on one hand while standing above glowing light bulbs positioned on the floor; in another he attempts to hang vertically from a tree branch over a running stream; in the third he tries to balance on his right leg so his left leg and torso are horizontal. In all three, gravity inevitably defeats him. These actions seem on film to be Buster Keatonish – funny but tragic. Even Bas Jan Ader’s most famous image, of him weeping with tears trickling down his face, is connected to the themes of failure and gravity.

Nearby Cleland has positioned another b/w film, a recent, very elegant work by German artist Hanna Schwarz. It shows her dressed in white shirt, androgynous eighties rockstar haircut, grey jeans and boots, making quick walking motions or foot actions, or holding careful Nijinsky-like positions with her torso, head and arms in profile like a hieroglyphic. These sections are all sequenced to be accompanied by a soundtrack of tap dancing or clacking temple blocks, sometimes in sync, but mostly not. Often she takes up minotaur poses with her head pulled under and her arms extended like horns. With the soundtrack the images have a Spanish flavour.

In one scene, she like Bas Jan Ader, balances on one leg, not frontally, but like a reaching ice skater – in profile. In another she adopts a golf putting pose. Tongue in cheek humour permeates every image she presents.

With the room of installed ‘dematerialised’ sculptures by John Ward Knox we move from a trajectory of sequential filmic experiences (where we are stationary) to an awareness of our own bodily movements. We now circle within a space shared with understated static objects that modify the architecture - and so lock into our own perceptions of form, light, shadow, as demonstrated by his intervening materials that play with the sides and corners of the classic white cube.

Using the first gallery wall just inside the door, Ward Knox mocks the materiality of paint by carving into plaster on its surface to render in relief a slashing streaky mark made by a horizontally moving housepainting brush. It also has little vertical dribbles running off its bottom edge. Gentle plasticity, light and shadow create this shallow-relief, meticulously sanded drawing that forces us to closely examine the brightly-lit wall’s plane and the subtle projection of its surface.

The two corners Ward Knox treats with bent wire and delicate silver chain, one with the two joined to form a continuous arabesque, the other with the two curved materials straddling the gap between the intersecting planes separately. Shadow in this artist’s hands becomes another substance which accentuates traces from materials that in bright light almost become invisible.

Nextdoor inside the main Te Tuhi gallery space, we find spotlit in its centre a small circular wooden stage with steps. This serves as a seat for the huge five screen Alex Monteith panorama on three walls, and is also the platform for the Eddie Clemens interactive kinetic sculpture.

In its middle is a spinning Scalextric slot-car track, complete with mini safety fence that surrounds a bowl of black oil. The track starts moving when you step on to the stairs. On its upper curved slot is a small blue and white sedan (with its own tiny orange light under its chassis) that moves independently of the backwards turning track – so that it can even accelerate forwards faster.

Clemens’ project is mesmerising through the way you automatically attempt to analyse the paradoxical relationship of the moving track with the motion of the toy car, but in the context that Cleland has constructed around it, it also becomes a brilliant metaphor for the movement of the viewer doing the circuit in the Modern Physics space. A witty, schematicised, God’s eye view.

It is also a perfect foil to the spectacular acrobatics of the Monteith display, with the five cameras set looking out over each of the five pilot’s tracer streaming tails as the RNZAF Red Checkers stunt team perform a highly choreographed series of double loops, barrel rolls and ‘spaghetti-breaks’ – all co-ordinated with synchronised sound and simultaneous action.

The synchronised DVD loops start when the five planes take off in sequence and finishes after they’ve landed and manoeuvred to park on the runway. Not only is the work’s churning visceral sensation extraordinary (though personally I found the ‘firecracker’ aural component of her motorbike videos at AUT last year more bodily penetrating) but the colourful cloudscape and changing light is rivetting.

Philip Dadson’s DVD project is also aeronautically focussed, but using balloons - not speeding aircraft. Part of a much bigger version he made last year with seventeen colourful balloons and twenty-four musicians, this small two channel version with two balloons (and six green uniformed brass band members) focuses on the aerially viewed patchwork landscape more than the much faster Monteith work, with the two cameras aimed either across or down.

The thin, mournful, drawn out notes of the musical performances from tuba, trombone and trumpet players, with little melodic variation, make Dadson’s hovering music quite haunting. Like the leisurely moving balloons the music gently drifts - sometimes stopping, then restarting. Occasionally he has dubbed undertoning over the brass, using his own voice.

Dadson’s two screens are positioned at rightangles to each other, like the screens in the Gladwell work. In fact his moving coloured aerial images fit perfectly in the sequence between the Monteith and the Gladwell works, cleverly completing the ambulatory loop. Cleland has come up with something exceptional with this very special Te Tuhi show. All the individual ingredients individually and collectively add up to a great total experience. Everything is strong and memorable. A wonderful treat that you would be an absolute nitwit to miss.